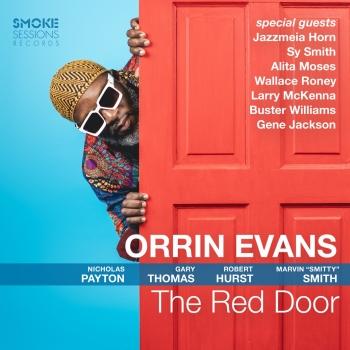

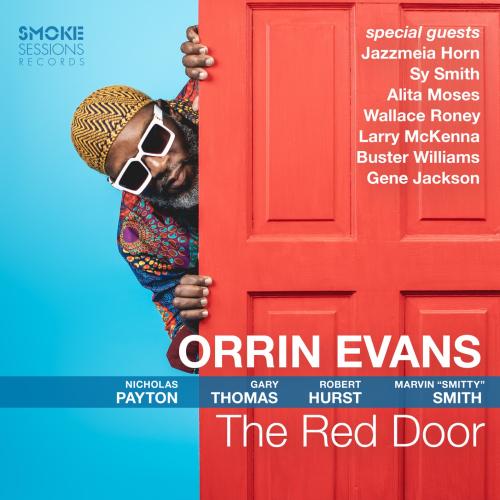

The Red Door Orrin Evans

Album Info

Album Veröffentlichung:

2023

HRA-Veröffentlichung:

16.06.2023

Das Album enthält Albumcover

- 1 Red Door 04:04

- 2 Weezy 07:11

- 3 Phoebe's Stroll 07:35

- 4 The Good Life 09:15

- 5 Big Small 04:36

- 6 Dexter's Tune 03:58

- 7 Amazing Grace 04:12

- 8 Feed the Fire 05:15

- 9 All The Things You Are 04:25

- 10 Smoke Rings 02:43

- 11 They Won't Go When I Go 05:22

- 12 I Have the Feeling I've Been Here Before 03:33

Info zu The Red Door

What’s behind THE RED DOOR? For pianist Orrin Evans, that question has come to symbolize the daring path his life and music have taken over the course of his three-decade career. On his latest album, he once again flings that door open, delighting in the collaborators, friends, inspiration, and history that he finds inside.

Growing up in the Pentecostal church, Evans explains, the color red came to signify the negative: think blood, sin, the temptation embodied in red light districts, all things infernal. Approaching a red door, then, is a daunting prospect. The image manifested for him recently when he overheard someone say, “I don’t see color” – itself something of a red flag.

“I’ve realized that along with red meaning ‘warning’ or ‘stop,’ it also represents so many beautiful things,” he says. “Roses are red, and Valentine’s hearts. So, I do see color, and we all should see color, but we shouldn't see the negative history that comes along with it. Instead, we need to allow ourselves the opportunity to walk inside and discover what’s behind the red door.”

Looking back, Evans has opened that door time and again, always with fortuitous results. There was the decision to pursue a life in jazz, the initial red door that led to a series of others: summoning the courage to test his mettle in the notorious jam sessions at Ortlieb’s Jazzhaus in Philly; braving a move to New York with growing confidence but no sure prospects (“I didn't get a gig, but I got a wife,” he laughs); launching his own big band, a formidable undertaking that’s ended up garnering him two Grammy nominations; joining The Bad Plus, putting him under microscopic scrutiny, the striking out on his own again despite the band’s ongoing success.

Many of the musicians who join Evans on THE RED DOOR connect to those periods of discovery and growth. The album features two core bands: one the rhythm section of bass legend Buster Williams and veteran drummer Gene Jackson, joined by the late trumpet master Wallace Roney or Philly living legend Larry McKenna on tenor; the other a quintet with trumpeter Nicholas Payton, saxophonist/flutist Gary Thomas, bassist Robert Hurst and drummer Marvin “Smitty” Smith. In addition, the album features guest appearances by vocalists Jazzmeia Horn, Sy Smith, and Alita Moses.

“I could connect everybody on this record to something good that happened once I got beyond all the fear and said, ‘F**k it, I'm going to go through this door and see what happens,’” Evans asserts. “This is a tribute to all of those people who have contributed to my history, development, and growth and are connected to the beauty I’ve found on the other side.”

In many cases, the elders on the album are artists whom Evans had long dreamed of working with, or acquaintances from the past whom he felt he was long overdue to reconnect with. Roney, who hired Evans early in the pianist’s career but whose path he hadn’t crossed in the intervening years, passed away in March 2020, an early casualty of the pandemic, bringing home the urgency of working with these masters while they’re still among us.

COVID also claimed the great tenor titan Bootsie Barnes. Evans had originally planned to include Barnes with fellow Philly legend Larry McKenna, who was Evans’ first music theory teacher. McKenna unfurls a simmering, lyrical solo on “The Good Life,” his first meeting with the great Buster Williams. “All the Things You Are,” meanwhile, brings West Philly natives Roney and Gene Jackson together for the first time since both were featured on Joey DeFrancesco’s 1990 big band album Where Were You? – and in that case, the two were never in the studio together. The album closes with the aching ballad “I Have the Feeling I’ve Been Here Before,” rendered by the trio of Evans, Hurst, and Smith.

The Red Door opens with the title track, which Evans originally recorded with The Bad Plus on 2019’s Activate Infinity. Payton had recorded with Evans as a guest with the collective trio Tarbaby, but Thomas’s presence finally makes up for the saxophonist’s inability to make the session for Evans’ 2002 Palmetto debut, Meant to Shine. Early on, Evans recalls, “Gary was on the other side of that door for me because he was working with Uri Caine and Ralph Peterson.”

Hurst, Smith, and Jackson all harken back to the progressive 80s jazz sound that the pianist was reared on, working with the likes of Kevin Eubanks and Branford Marsalis. Evans had only worked with Hurst and Smith once apiece – the drummer on a never-released Kevin Eubanks recording, the bassist on a Terri Lyne Carrington performance. “I don’t apologize for loving that 80s music and 80s sound,” Evans insists.

“Weezy” and “Phoebe’s Stroll,” the latter of which pares the quintet back to a swaggering trio, are both named for Evans’ godchildren – Sean Jones’ daughter Phoebe and Eloise, the daughter of his booking agents. The trio also essays the lovely “Dexter’s Tune,” a Randy Newman composition from the soundtrack of the 1990 film Awakenings. The quintet reconvenes for Geri Allen’s “Feed the Fire,” and Ralph Peterson Jr.’s “Smoke Rings,” both composed by influential figures lost too soon.

As always, Evans’ recording dates tend to adhere to a liberal open-door policy (red or otherwise), in this case, welcoming three gifted vocalists to the ever-growing village. Jazzmeia Horn gives an impassioned reading of Bill McHenry’s lyric for Evans’ “Big Small,” which originally appeared on his 2012 trio album Flip the Script. Sy Smith took a break from her busy touring schedule with Chris Botti to sing Geri Allen’s arrangement of “Amazing Grace,” while Alita Moses duets with Evans on a spare, compelling rendition of Stevie Wonder’s “They Won’t Go When I Go.”

The musicians with whom he collaborates may not always know what to expect when they walk into an Orrin Evans studio date, but he flings that red door open for them. Now it’s the listeners’ turn to enter. “It's a swinging party on the inside.”

Orrin Evans, piano

Nicholas Payton, trumpet (1, 2, 5, 10)

Gary Thomas, tenor saxophone (1, 5, 10); flute (2)

Robert Hurst, bass (1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 12)

Marvin “Smitty” Smith, drums (1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 12)

Wallace Roney, trumpet (9)

Larry McKenna, tenor saxophone (4)

Buster Williams, bass (4, 9)

Gene Jackson, drums (4, 9)

Jazzmeia Horn (5)

Sy Smith, horn (7)

Alita Moses, horn (11)

Orrin Evans

During his kaleidoscopic quarter-century as a professional jazz musician, pianist Orrin Evans has become the model of a fiercely independent artist who pushes the envelope in all directions.

Evans has ascended to top-of-the-pyramid stature on his instrument, ranked the #1 “Rising Star Pianist” in the 2018 DownBeat Critics Poll. GRAMMY nominations for the albums The Intangible Between and Presence (Smoke Sessions), by Evans’ raucous, risk-friendly Captain Black Big Band, cement his bona fides as a bandleader and composer.

A deft tune deconstructor, Evans commands vocabulary across a broad timeline of swinging, blues-infused hardcore jazz and spiritual/avant garde jazz dialects, as well as the Euro-canon, and conveys his stories with the intuitive spontaneity of an ear player. He projects an instantly recognizable sound, sometimes creating flowing rubato tone poems, sometimes embodying the notion that the piano comprises 88 tuned drums.

Evans’ stylistically polyglot compositions – influenced by the expansive, individuality-first Black Music culture of his native Philadelphia and a decade playing Charles Mingus’ music in the Mingus Big Band – create an environment of “structured freedom” that instigates personnel to push the envelope in all his multifarious leader and collaborative projects. These include the Eubanks Evans Experience (with guitarist Kevin Eubanks); the Brazilian unit Terreno Comum; Evans’ working trio with bassist Luques Curtis and drummer Mark Whitfield; Jr.; and Tar Baby, a 20-year collective trio with bassist Eric Revis and drummer Nasheet Waits.

Evan’s discography includes over 20 albums, the most recent being Magic of Now (Smoke Sessions). One of Tar Baby’s two 2022 releases will be released on his imprint, Imani Records, which he founded in 2001 and relaunched in 2018.

An influential educator, Evans is devoted to passing the torch to new generations. His students include alto saxophonist and Blue Note artist Immanuel Wilkins and GRAMMY-nominated pianist Brandon Goldberg.

In the booklet notes for Orrin Evans’ second album, Captain Black, recorded in 1998, the pianist, then 23, made a remark that encapsulates the aesthetic he’s followed ever since on his kaleidoscopic artistic journey. “I go head-first for a lot of things,” Evans said. “I like to stretch out. Wherever the music takes me, I’m going there.”

That attitude backdrops the title of Evans’ 20th album, Magic of Now (Smoke Sessions), which documents a livestream engagement at Smoke Jazz Club during the second weekend of December 2020. Evans and a multi-generational cohort of A-list partners – first-call New York bassist Vicente Archer; iconic drummer Bill Stewart; and dynamic rising star alto saxophonist Immanuel Wilkins, now 23 himself – generate an eight-piece program that exemplifies state-of-the-art modern jazz. From the first note to the last, the quartet, convening as a unit for the first time, displays the cohesion and creative confidence of old friends, mirroring the leader’s predisposition for finding beauty in the heat of the moment.

As he does on five prior albums for Smoke Sessions, eight self-issued albums on Imani Records (his imprint), and earlier recordings for Criss Cross, Palmetto and Posi-Tone, Evans guides the creative flow from the piano, showcasing his authoritative mastery of his instrument and deep assimilation of the fundamentals. A deft tune deconstructor, he traverses a broad timeline of the vocabularies of swinging, blues-infused hardcore jazz and spiritual jazz/avant garde jazz traditions, as well as the Euro-canon, with the intuitive spontaneity of an ear player. He projects an instantly recognizable sound, sometimes eliciting flowing rubato poetry, sometimes evoking the notion that the piano comprises 88 tuned drums. It’s taken a while, but the jazz gatekeepers have noticed – in 2018, Evans topped the “Rising Star Pianist” category in DownBeat Critics Poll, and a feature article about him appears in DownBeat’s September 2021 edition.

Evans’ stylistically polyglot compositions – influenced by the expansive, individuality-first Black Music culture of his native Philadelphia and by a decade playing Charles Mingus’ beyond-category music in the Mingus Big Band – similarly postulate an environment of “structured freedom” that instigates the personnel to push the envelope in all his multifarious leader and collaborative projects.

In none of Evans’ units of recent years is that no-holds-barred attitude more prevalent than the Captain Black Big Band, a communitarian-oriented ensemble whose fourth and latest album is The Intangible Between (Smoke Sessions), preceded by Presence (Smoke Sessions). Both earned Grammy nominations.

Evans and his wife, Dawn, founded Imani in 2001 as a vehicle for Evans to release leader projects that couldn’t otherwise find a home. The label relaunched in 2018, with the release of albums by saxophonist Caleb Wheeler Curtis and bassist Jonathan Michel.

In creating and operating Imani Records, in organizing bands that navigate streams of expression outside his wheelhouse, in booking venues from the Philadelphia room Blue Moon (where he ran a Monday jam session from his late teens until early twenties) to the D.C. Jazz Festival (which recently appointed him Artist in Residence), Evans drew inspiration from his parents. His father, Donald Evans, was a playwright and educator who self-produced his plays; his mother, Frances, an opera singer who put on concerts in various alternative venues.

In addition to teaching on the bandstand, Evans has conveyed knowledge in more formal contexts. For a full year, he curated weekly jazz curriculum in Philadelphia public schools, sponsored by the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts’ Jazz Standards programming division. For three years he instructed high school students at Germantown Friends School. He’s served on the faculty of Connecticut’s Litchfield Jazz Camp since 2013 (one student was the phenomenal 15-year-old pianist Brandon Goldberg) and the Kimmel Center Jazz Camp, headed by bassist/producer Anthony Tidd (where Evans taught Immanuel Wilkins).

“I’m learning every day,” Evans says. “If someone calls to ask if I have a Brazilian project, I won’t say no. I’ll dive into it, call some great Brazilian musicians and put together a Brazilian project. If someone asks if I have a big band, I’ll educate myself and try to put a big band together. I don’t know how to sit and wait.”

Dieses Album enthält kein Booklet