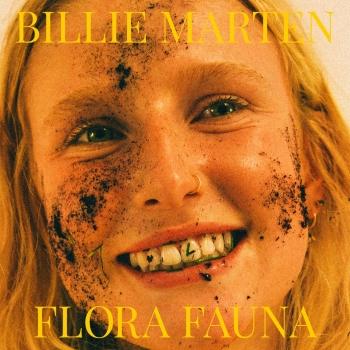

Billie Marten

Biographie Billie Marten

Billie Marten

There is a photograph hanging above the piano in Billie Marten’s family home just outside Ripon that shows the nearby Yorkshire Dales. There was something in its wildness, the untrodden vastness of nature and space, that always captured Marten’s imagination; the possibility of what might lie out there in the world. “I used to sit there and think of stupid little stories about that photograph,” she says. “Then one of the first songs I ever wrote when I was about nine was called I’m Gonna Run – and it was all about getting on a train and leaving and exploring.”

The desire to run and the opposing impulse to remain rooted in the family and the landscape that she loves, are crucial to Marten’s songwriting. At just 17, she speaks of her hope to carry on her studies, of the longing sometimes to “be where the noise is”, the feeling that “there’s so many places I haven’t been and so many things I haven’t done and I’ve got to do them all”. But she talks, too, with great tenderness of the village she resides, of the contentedness of family life. “I think it’s really important to stay where you are and where you know, so you’ve got that space,” she says. “I contradict myself a lot.”

Marten’s debut sits, pleasingly, in precisely that contradictory place. So while she might sing sometimes of uncertainty, the want of confidence or a need for boldness, she does so with a lyrical and musical articulacy that seems to belong to a far older soul. She can at one moment be singing the life of Emily Bronte, and the next exploring experimental washes of sound, drum clicks, synths. Her music is by turns delicate, confessional, inquisitive.

Marten inherited a love of language from her parents — from a father who loves reading and a mother who writes poetry, and a home that was filled with music — with piano and guitar and the albums of Damien Rice, John Martyn, Joan Armatrading, Joni Mitchell, Loudon Wainwright. When Marten began to play and write songs it was fuelled, she says, by nothing more than “wanting to join in with the rest of the family.”

That she was rather good at it was soon apparent. Her first show, at the age of 12, took place on a bandstand on Ripon racecourse. “It was raining,” she recalls. “Two people were there. One of them was my parent, and the other was a guy in an ice cream van. It was a fete or something but nobody was there because it was so miserable. I’d borrowed my Uncle’s speakers and a guitar that was too big for me, and I played two songs I’d written myself and some covers — Doll Parts by Hole, a Joanna Newsom song and a Kate Rusby. I really don’t think I enjoyed it.”

Her evolution from rain-sodden bandstand troubadour to radio star came via a series of online videos — first there were the videos her mother posted on Youtube so that her grandparents in France could see her play. Then there were the two songs she performed for a Harrogate session called Ont Sofa, which Marten remembers only as two cameras pointing in her face while she played a Lucy Rose cover and one of her own songs on her Dad’s guitar. “But then something happened with those videos,” she says. “My manager’s son somehow found them and played them to her. And then they came up North to meet me.”

In the five years between, Marten has been gently helped to find her way as a songwriter — early co-writing sessions with Fiona Bevan (famed for her work with Ed Sheeran) changed the way she looks at chords, but also gave her a confidence in her own voice. Likewise the “tiny gigs with just 12 people” in which she would appear between a rock band and a reggae act from Otley, spending “twenty minutes fumbling awkwardly with my guitar” helped galvanise her for the live performances she plays today. So while in person Marten can seem quite fragile and unsure of herself, in song she finds a strength and a resilience. “I’ve never been good at speaking to people,” she says. “I think when I sing something it’s easier.”

As well as writing with Bevan and her bandmate Jason Odle, Marten has worked closely with her producers Rich Cooper and Cam Blackwood. Their differing styles of working have kept her inspired, she says — Cooper’s studio well-planned and well-plotted; Blackwood’s approach more haphazard, but fueled by a shared love of Hemingway, Sufjan Stevens, Elliott Smith. She lights up when she talks of time spent making these songs. “Recording is the happiest time for me,” she says. “I really treasure it.”

Their themes and influences prove a broad sweep of her life and preoccupations — Robert Plant, Yorkshire, falling in and out of love with London, greed, the hurtling speed of modern life, insecurity, sunburn, loneliness and experiments in sound and mood and space. It is as rich and full a portrait of what it means to be a young woman as one could hope to hear. On album opener La Lune, she’s telling of the heat and overwhelmingness of life for a 17 year old girl, on Milk & Honey she stands confused by her peers’ devotion to money and material goods, while on Lionhearted she’s finding her own kind of rage and ferocity.

But for every brighter, bolder moment there comes a counterpoint — the arresting Teeth, for instance, which she wrote and recorded at home on the family piano around Christmas time, when she was by her own admission “Not in a good head space. I have a lot of problems with mental health, and there’s some months where you’re not human and some months where you’re fine. I think too much. That’s my issue. But this is a reflective song, about how things are and how they should be.” To record it, they swaddled the family piano in blankets to dampen its brightness, and opened the back door to let the birdsong in.”

The album’s closing song is a cover of It’s A Fine Day, the poem written by Edward Barton and recorded by his wife Jane, later made famous as a release for Opus 3. “I don’t know why they let me record that,” she says, sounding glad yet baffled. “It’s one of our family songs — I just always heard it throughout the house and thought it was the loveliest thing. So one day I went up to my room, opened garage band, which I’d never used before, got a terrible mic to record and then put a telephone vocal effect on it. And you can hear the birds and my dad lawn-mowing in it. But I thought it was so beautiful, and it’s something I love and it’s always been there.”

She talks then about her home, of the light that fills her room at a particular time of day “and then everything just turns orange for 15 minutes”, of the sparrows in the garden, and the trees beyond her window. “I have a thing,” she laughs, “about windows.” And really there is no better way to think of Marten — a young woman on the brink of adulthood and the wide world beyond, a songwriter looking out, and looking in.