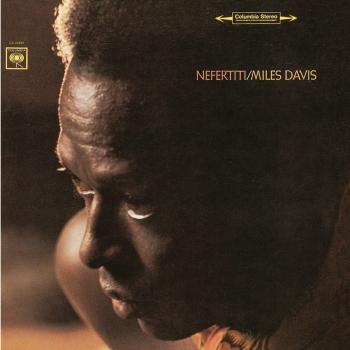

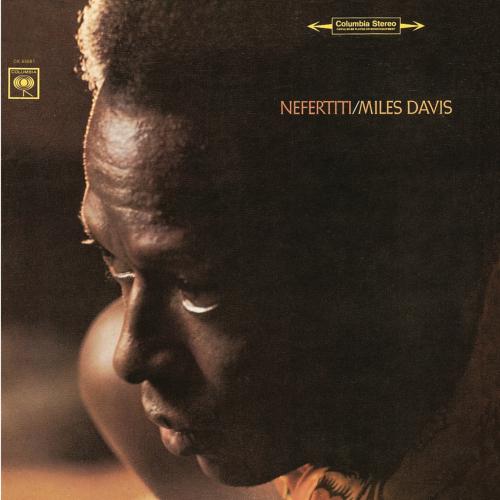

Nefertiti (2023 Remaster) Miles Davis

Album info

Album-Release:

1968

HRA-Release:

20.01.2023

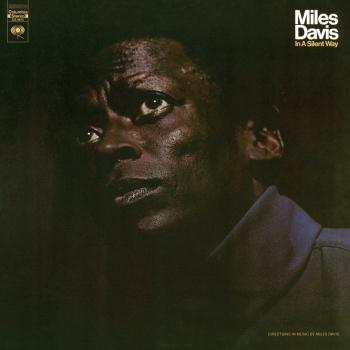

Album including Album cover

I`m sorry!

Dear HIGHRESAUDIO Visitor,

due to territorial constraints and also different releases dates in each country you currently can`t purchase this album. We are updating our release dates twice a week. So, please feel free to check from time-to-time, if the album is available for your country.

We suggest, that you bookmark the album and use our Short List function.

Thank you for your understanding and patience.

Yours sincerely, HIGHRESAUDIO

- 1 Nefertiti (2023 Remaster) 07:52

- 2 Fall (2023 Remaster) 06:35

- 3 Hand Jive (2023 Remaster) 08:54

- 4 Madness (2023 Remaster) 07:31

- 5 Riot (2023 Remaster) 03:05

- 6 Pinocchio (2023 Remaster) 05:06

Info for Nefertiti (2023 Remaster)

By 1966, the producers at CBS Records—that was most often Teo Macero—had learned to roll tape early and often at a Miles Davis session, catching rehearsal and first-takes as well as the final sessions. In some cases, like the title track of Nefertiti in the first week of June 1967, it truly paid off. What was intended to be the initial rehearsal of “Nefertiti,” a new, 16-bar tune by Shorter, found the group repeating the melody line, over and over, tugging and pulling at the tune, embellishing it at will—yet never veering off to solo over the harmony as per standard jazz practice.

And in fact, that was how they recorded “Nefertiti,” as a modern jazz bolero, with the melody itself serving as a mantra of sorts with Williams’ rhythmic ebb and flow steering the performance (producer/saxophonist Bob Belden called it a “drum concerto as composition.”) In June 1967, that light-bulb moment immediately led to the second, final take, and injected a new sense of structural freedom not only into the Quintet’s repertoire, but by example, the jazz scene in general. “Nefertiti” also became the linchpin—with its haunting beauty and cyclic form—to an album filled with groundbreaking performances.

“Hand Jive” is another feature for Williams, written and propelled by the drummer, a taste of the more funk-inflected style he would lean on in 1968 and after. “Fall” and “Pinnochio” are Shorter compositions, the former a moodier companion piece—in feel and form—to “Nefertiti.” The latter offers a jaunty, swinging take on yet another catchy Shorter theme, the Quintet using it at the open and close of the tune, and as an interlude between solo statements by Miles, Shorter, and Hancock.

The two Hancock compositions reveal how Miles only took what he felt was needed—the released take of “Madness” for example only uses the last eight bars of the tune, the cadence section before firing into improvisations—the theme of “Riot” is equally brief, and is powered by the Quintet’s penchant for dynamic outburst, and William’s Latin-spiced drive.

The Quintet, by the time of this, their fourth studio album, is venturing forth in new musical territory, breaking ground for generations to come. It also stands as a departure point for Miles: Nefertiti is the last purely acoustic jazz album he records as a leader. Starting with his next recording and all that follow, he will invite electric, amplified instruments to the party, an ever-increasing reliance on non-traditional instrumentation that has a seismic influence on the jazz scene.

"Nefertiti, the fourth album by Miles Davis' second classic quintet, continues the forward motion of Sorcerer, as the group settles into a low-key, exploratory groove, offering music with recognizable themes -- but themes that were deliberately dissonant, slightly unsettling even as they burrowed their way into the consciousness. In a sense, this is mood music, since, like on much of Sorcerer, the individual parts mesh in unpredictable ways, creating evocative, floating soundscapes. This music anticipates the free-fall, impressionistic work of In a Silent Way, yet it remains rooted in hard bop, particularly when the tempo is a bit sprightly, as on "Hand Jive." Yet even when the instrumentalists and soloists are placed in the foreground -- such as Miles' extended opening solo on "Madness" or Hancock's long solo toward the end of the piece -- this never feels like showcases for virtuosity, the way some showboating hard bop can, though each player shines. What's impressive, like on all of this quintet's sessions, is the interplay, how the musicians follow an unpredictable path as a unit, turning in music that is always searching, always provocative, and never boring. Perhaps Nefertiti's charms are a little more subtle than those of its predecessors, but that makes it intriguing. Besides, this album so clearly points the way to fusion, while remaining acoustic, that it may force listeners on either side of the fence into another direction." (Stephen Thomas Erlewine, AMG)

Miles Davis, trumpet

Wayne Shorter, tenor saxophone

Herbie Hancock, piano

Ron Carter, double bass

Tony Williams, drums

Digitally remastered

Trumpeter Miles Davis grew up in East St. Louis, Illinois, just across the river from St. Louis, Missouri. His parents were affluent, and had the means to support his musical studies as a boy. He began playing the cornet at age nine, and received his first trumpet at around twelve or thirteen. He studied classical technique, and focused mainly on using a rich, clear tone, something that helped define his sound in later years.

As a teenager, he played in various bands in St. Louis, which was rich with jazz, as big bands often stopped there on tours throughout the Midwest and southern states. The most important experience he had was when he was asked to play in the Billy Eckstine band for a week as a substitute. The group included Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Sara Vaughan. After playing with these stars, Davis knew he had to move to New York to be at the heart of the jazz scene.

In Pursuit of Parker:

In 1944 Davis moved to New York City where he had earned a scholarship to study trumpet at the Juilliard School of Music. Upon arriving however, he sought after Charlie Parker, and meanwhile spent all of his time in jazz clubs listening to bebop. He was transfixed on the music, and grew utterly bored with his classical studies. After less than a year at Juilliard, he dropped out and tried his hand at performing jazz.

Although not particularly stunning, his playing was good enough to finally attract Charlie Parker, and Davis joined his quintet in 1945. He was often criticized for sounding inexperienced, and was compared unfavorably to Dizzy Gillespie and Fats Navarro, who were the leading trumpeters at the time. Both boasted stellar technique and range, neither of which Davis possessed. In spite of this, he made a lasting impression on those who heard him, and his career was soon set aloft.

Cool Jazz and a Rise to Fame:

Encouraged by composer and arranger Gil Evans, Davis formed a group in 1949 that consisted of nine musicians, including Lee Konitz and Gerry Mulligan. The group was larger than most bebop ensembles, and featured more detailed arrangements. The music was characterized by a more subdued mood than earlier styles, and came to be known as cool jazz. In 1949 Davis released the album Birth of the Cool (Captiol Records).

Change of artistic direction became central to Davis’ long and increasingly influential career. After dabbling in hard bop as a leader on four Prestige recordings featuring John Coltrane, he signed with Columbia records and made albums that featured Gil Evans’ arrangements for 19-piece orchestra. These were Miles Ahead, Porgy and Bess, Sketches of Spain, and Quiet Nights. He rose in popularity with these recordings, in part due to his signature sound, which he often enhanced by using a Harmon mute.

Kind of Blue and Beyond:

In 1959 Davis made his pivotal recording, Kind of Blue. It was a departure from all of his previous projects, abandoning complicated melodies for tunes that were sometimes only composed of two chords. This style became known as modal jazz, and it allows the soloist expressive freedom since he does not have to negotiate complex harmonies. Kind of Blue also featured John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley, and Bill Evans. The album is one of the most influential in jazz, and is Columbia Records’ best-selling jazz record of all time.

In the mid 1960s Davis changed directions again, forming a group with Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Tony Williams, and Ron Carter. This group was known for the excellence of each individual member, and also for its unique performance approach. Each night the tunes would sound different, as the musicians would sometimes only loosely adhere to the song structures, and often transition from one right into the next. Each player was given the chance to develop his solos extensively. Like all of Davis’ previous groups, this quintet was highly influential.

Late Career:

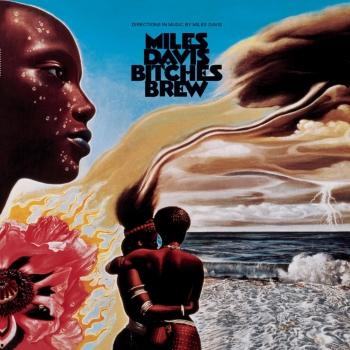

Despite health problems, drug addiction, and strained personal relationships, Davis continued to play, changing his approach with each new project. In the late 60s and 70s, he began to experiment with electronic instruments, and grooves that were tinged with rock and funk music. Two famous recordings from this period are In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew. By the time the 1980s rolled around, Davis was not only a jazz legacy, but a pop icon, whose music, persona, and fashion style were legendary.

Davis died in 1991, as perhaps the most influential jazz artist ever. His vast body of work continues to be a source of inspiration for today’s musicians. (Jacob Teichroew, About.com Guide)

This album contains no booklet.