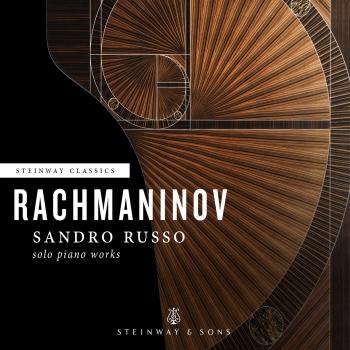

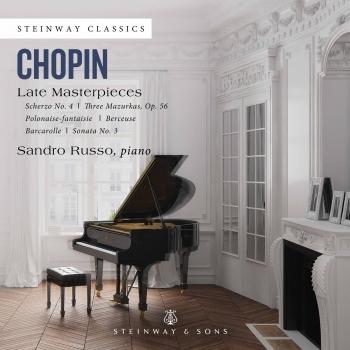

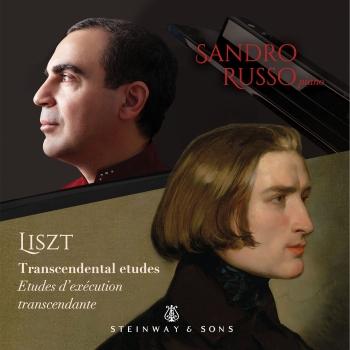

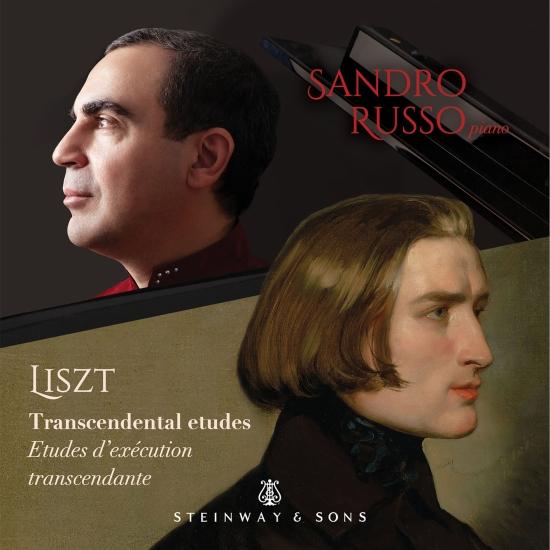

Liszt: Études d'exécution transcendante, S. 139 Sandro Russo

Album info

Album-Release:

2024

HRA-Release:

03.05.2024

Label: Steinway and Sons

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Instrumental

Artist: Sandro Russo

Composer: Franz Liszt (1811-1886)

Album including Album cover

- Franz Liszt (1811 - 1886): Études d'exécution transcendante, S. 139:

- 1Liszt: Études d'exécution transcendante, S. 139: No. 1, Preludio00:54

- 2Liszt: Études d'exécution transcendante, S. 139: No. 2, Molto vivace02:23

- 3Liszt: Études d'exécution transcendante, S. 139: No. 3, Paysage04:45

- 4Liszt: Études d'exécution transcendante, S. 139: No. 4, Mazeppa07:46

- 5Liszt: Études d'exécution transcendante, S. 139: No. 5, Feux follets03:53

- 6Liszt: Études d'exécution transcendante, S. 139: No. 6, Vision05:33

- 7Liszt: Études d'exécution transcendante, S. 139: No. 7, Eroica05:05

- 8Liszt: Études d'exécution transcendante, S. 139: No. 8, Wilde Jagd05:25

- 9Liszt: Études d'exécution transcendante, S. 139: No. 9, Ricordanza10:58

- 10Liszt: Études d'exécution transcendante, S. 139: No. 10, Allegro agitato molto04:45

- 11Liszt: Études d'exécution transcendante, S. 139: No. 11, Harmonies du soir09:39

- 12Liszt: Études d'exécution transcendante, S. 139: No. 12, Chasse-neige05:57

Info for Liszt: Études d'exécution transcendante, S. 139

The genesis of the Transcendental Etudes––which spans a quarter century since these works’ earliest ancestor, etude en douze exercices––is a rather intricate and laborious one. Liszt’s first venture into the etude as an art form took place when he was only 13 years old. Despite his tender age, his first set of 12 etudes evinces strong and well-defined thematic outlines that would constitute the basis for both his Grandes etudes and etudes d'execution transcendante (or Transcendental Etudes). Apart from the motivic significance of the earlier works, as well as their tonal design (which is the same model for the following two versions), their technical apparatus is hardly innovative; they are, in fact, more reminiscent of Clementi, Cramer, Moscheles, or Czerny’s piano writing.

A very significant breakthrough in Liszt’s compositional and concert career occurred in the 1830s, when he first heard Paganini perform in Paris. The level of astonishment provoked by the Italian violinist was well summarized in one of Liszt’s letters:

For a whole fortnight my mind and my fingers have been working like two lost souls....In addition, I practice four to five hours a day of exercises (thirds, sixths, octaves, tremolos, repetition of notes, cadenzas, etc.). Ah! Provided I don’t go mad, you will find in me an artist!

Paganini’s “demonic” virtuosity is unquestionably reflected in all of the astounding technical escalations manifested in Liszt’s new Grandes etudes from 1838; indeed, every resource in the realm of piano technique gets fully exploited to the limits of human possibilities. However, this oversaturated display of virtuosity somewhat backfired, as far as the aesthetic content of these particular works was concerned. Apart from the fact that only Liszt himself could perform them, it is, in retrospect, as if the overabundance of pianistic pyrotechnics exhibited in these Etudes had actually obscured their musical worth.

A review of the newly published Grandes etudes by no less than Robert Schumann earned them the distinction of “Etudes of storm and dread, for at most ten or twelve players in the world.” In the same publication, On Music and Musicians, Schumann goes on to opine that Liszt’s exaggerated virtuosity may have proved detrimental to his evolution as a composer. He adds that “the original simplicity which is natural to the first flow of youthful talent is almost entirely suppressed in the present form of the work.”

Whether one agrees or not with the latter statement, Schumann’s advice to Liszt that he “must subject his compositions to a reverse process––must simplify rather than render them more weighty,” is of great relevance to the Grandes etudes’ final revision in 1851, published a year later under the title etudes d’execution transcendante.

This final version of these Etudes reflects very significant changes in Liszt’s artistic life, his official retirement from the concert stage four years earlier being one of them. Without a doubt, the etudes d’execution transcendante are a refinement of the Grandes etudes, so much so that Liszt thereafter wanted to completely disassociate himself from the latter. The fact that Liszt’s etudes d’execution transcendante came to life during the so-called “Weimar Years” (often referred to as the period of the composer’s maturity) was not a mere coincidence; it was as if Liszt felt he had to redeem himself, somehow, from the criticism he’d received during his “virtuoso years,” thus proving to the world he could write as a master composer.

The Transcendental Etudes well embody some of the most significant traits of Liszt’s prolific “Weimar” period: the quest for new aesthetics of sound; an evident simplification of textures (as suggested by Schumann); and a stronger-than-ever penchant for programmatic elements derived from literature, nature, and the visual arts. Liszt also brought a new, truly poetic dimension to these Etudes by adding highly evocative titles to ten of them.

Some of the Transcendental Etudes evoke nature in its idyllic beauty and fierceness (i.e., “Paysage” and “Chasse-neige,” respectively); mythological figures (“Wilde jagd”); legends/heroes (“Mazeppa,” as portrayed in Victor Hugo’s Les Orientales, or “Vision,” believed to represent Napoleon’s funeral procession); ghostly phenomena (“Feux follets”); while others evince more harmonic lushness and lyricism (“Ricordanza” and “Harmonies du soir”).

As the word “Transcendental” implies, Liszt is more concerned with tailoring the etude art form to the drama and visionary content each piece represents, rather than limiting it to a given technical aspect; he uses the latter more as a point of departure. Each of his Transcendental Etudes, in fact, becomes like a “tone poem.” Even the first Etude, “Preludio,” is hardly a “warm up” piece to plunge into the cycle, but rather a work with a full narrative arch––despite its being less than a minute long! The later Etudes, with their more poetically descriptive titles, are undoubtedly more elaborate in their form and harmonic language.

Whether or not Liszt may have conceived the 12 Transcendental Etudes to be performed as a cycle, their programmatic elements, along with the intricacy of some of their narratives, could give one almost the sense of an entire opera’s being performed at the piano! After all, it was Liszt who had invented the modern piano recital. In any event, what seems clear is that Liszt chose to eschew conventional didactics and craft highly evolved concert pieces designed to evoke deep emotions in his listeners. (Sandro Russo)

Sandro Russo, piano

Sandro Russo

Acclaimed for his profound sense of poetry and distinctive style, Sandro Russo has been in demand as a soloist in many venues around the world. He unanimously receives accolades for his sparkling virtuosity and his playing has often been referred to as a throwback to the grand tradition of elegant pianism and beautiful sound. Garrick Ohlsson referred to Mr. Russo as “an excellent pianist with good sound, technique and range of styles,” while Abbey Simon praises him as "an artist to his finger tips...musical, intuitive, and a master of the instrument.”

Born in San Giovanni Gemini, Sicily, Mr. Russo displayed exceptional musical talent from an early age. In 1995, he graduated summa cum laude from the V. Bellini Conservatory and earned the Pianoforte Performing Diploma from the Royal College of Music in London ‘with honors’. While still a student, he won top prize awards in numerous national and international competitions, including Senigallia and the Ibla Grand Prize. During that time, he performed in some of the country’s most reputable concert halls.

Soon after Mr. Russo came to the United States in 2000, he won the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra Concerto Competition, and performed Liszt’s A major Concerto with Maestro David Gilbert at the Bergen Performing Arts Center in Englewood, NJ. Early in 2002, Mr. Russo gave an acclaimed Chopin recital at the prestigious Politeama Theatre in Palermo, Italy, and later appeared at the Nuove Carriere Music Festival, an international showcase for the world’s most promising young musicians.

Mr. Russo has performed in such prestigious concert halls as the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, the Konzerthaus Berlin, Weill and Zankel halls at Carnegie Hall, Salle Cortot in Paris and Teatro Politeama in Palermo. His recitals include performances for The Rachmaninoff Society, the Dame Myra Hess series in Chicago, Concerts Grand in Santa Rosa (CA), the American Liszt Society, the Houston International Piano Festival, the Husum Festival of Piano Rarities in Germany and the Chetham's International Piano Festival in Manchester (U.K.), among others. In November 2010 the Italian Academy Foundation presented Mr. Russo in a sold-out Chopin & Schumann anniversary concert at Carnegie Hall. His performances have aired on all the major radio stations in the US, the BBC Radio, RAI Radio 3 and the Slovakian TV.

Mr. Russo has also appeared as a soloist with the Slovak Philharmonic in Bratislava, The Jacksonville Symphony in Florida and The Brussels Chamber Orchestra at the opening gala of The Music Festival of the Hamptons in 2008. In July of the same year he gave three highly praised performances of the Rachmaninoff 3rd Piano Concerto on tour with the Orchestra Sinfonica Siciliana and he was also the featured soloist with the New York Asian Symphony for a Japan tour in 2009.

Mr. Russo’s extensive repertoire comprises well-known masterpieces of all periods as well as more obscure and challenging works of the piano literature, by such composer-pianists as Medtner, Sorabji, Cziffra and others. He has also been given the honor of premiering compositions by Lowell Liebermann, Paul Moravec, and Marc-André Hamelin. Lowell Liebermann wrote of him: “Sandro Russo is a musician's musician, and a pianist's pianist. There is no technical challenge too great for him, but it is his musicianship that ultimately makes the greatest impression. His interpretations reveal a unique and profound artist at work.”

In January 2009, Bechstein-America invited Mr. Russo to record a DVD on the historical 1862 Bechstein piano (#576) owned by Franz Liszt. In addition, the DVD “Sandro Russo Plays the Steinway CD-75 Horowitz Piano” represents the first recording on this legendary instrument after Horowitz’s death. Mr. Russo’s latest recordings, Scarlatti Recreated and Russian Gems – Piano Rarities, released in September 2013 and January 2014 respectively, on the Musical Concepts label have received universally critical acclaim. Sandro Russo is a Steinway Artist.

This album contains no booklet.