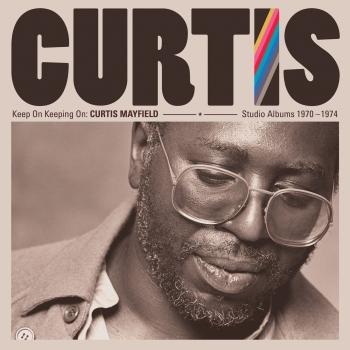

Curtis Mayfield

Biography Curtis Mayfield

Curtis Lee Mayfield

made his first recordings in 1958 as a member of a Chicago Soul/R & B group, The Impressions. He was 16, from the city’s notorious Cabrini Green Housing Projects. He was strictly a backup singer with the group – no guitar, no production, no songwriting. This would change, and sooner than later.

Mayfield made his last recording, “New World Order,” in 1995 after four decades of hit making as a solo artist, producer, composer and as a symbol for Black Pride and Black Capitalism within the music industry. Mayfield’s last go round in the studio was an example of courage and will. Paralyzed following an on stage accident, he recorded one line of a song at a time, lying on his back to allow his diaphragm to work and breath to get into his lungs.

“He broke his back but not his spirit,” says his widow Altheida Mayfield.

The music that surrounded and informed Curtis Mayfield, born 1942, at an early age came via his grandmother’s Travelling Soul Spiritualists’ Church, Gospel music and the rich mother lode that was Chicago’s electric blues scene. A guitar, discovered at age seven in a closet in the small apartment where he lived with his mother and seven siblings, changed everything. He played some piano but the guitar was different, very personal. “…like another me,” he said. Mayfield literally transferred his piano knowledge to his new instrument. Childhood friend, singer Jerry Butler noted: “He used to love playing boogie woogie on the piano and he learned to play that in F sharp which meant he was playing all the black keys. That’s how he came about his unique sound on the guitar because he tuned it that way.” Mayfield used his eccentric open F sharp tuning for the rest of his career. He also became proficient on bass, drums and saxophones.

It was now evident that Mayfield’s future was music, his way out of poverty. Over family objections, he dropped out of high school, joining The Roosters, a group led by Jerry Butler. The name quickly became the more commercial The Impressions. Butler has observed: “There’s something called the Chicago Soul sound that began in the late Fifties. The Impressions pioneered that… and Curtis was the heart of The Impressions”; but not at first…

Chicago’s soul music, evolving in the 1960s, had its roots in gospel music, laid back and melody focused (“soft soul” is another term for the style). Horns and strings and high flying harmonies were part of it.

The first Impressions hit “For Your Precious Love” had Butler as co-writer and lead singer. The single hit the R & B charts and, more importantly for a black group, the pop charts. Butler, getting most of the credit, immediately went solo.

This was a good thing for Mayfield, allowing him his first taste of control and responsibility. He held the group together as lead singer, producer and writer and in 1961 the revamped Impressions had its first Mayfield-era hit, “Gypsy Woman.” For the rest of the decade the group remained hot with 14 Top 10 hits including an amazing run of five Top 20 songs in 1964 alone - the year that The Beatles arrived to give a hard time to everyone.

Mayfield perfected the group’s singular upper register work and himself remained devoted to the falsetto rather than the more usual model range. Johnny Pate, a jazz musician who worked with The Impressions, remembered its effect: “The group went into some high falsetto harmonic things that were really unheard of. Nobody had done it before. The amazing part was it’s all in tune, in perfect harmony, in tune…"

The business plan of black popular music in the 1960s was governed by dance music and love songs. But Mayfield had ideas that would place his music on a different track. Outside the recording world, Black America faced Civil Rights, inner city poverty, drug use and abuse and, unprompted, Mayfield addressed these matters the only way he knew how, through his music, a provocative step that turned him into a musical force for change in the Black community. Singer Mavis Staples (of the Staples Singers) defined this transformation: “[Curtis] had a long history of writing wonderful love songs that made you want to dance slow to in the basement. And then, all of a sudden, he went and wrote some of the best message songs that could be out there.”

Mayfield was angry over the disorder affecting his America but his music was delivered in a singular, subtle and intelligent way, layered with Gospel, R & B and soul, served Chicago style. Calling Mayfield “a giant of gentleness,” singer Sinead O’Connor observed that his music “used love and encouragement, not anger, to say important things.” Mayfield’s voice, aimed at the mainstream audience, could moderate any hostility in the lyric without destroying its significance. The message was for the people, not the radical. “These songs were an example of what has lain in my subconscious for years… the issues of what concerned me as a young black man….,” Mayfield said. And politics apart, Mayfield still wanted his chart hits.

In 1964 The Impressions had its biggest hit to date with the Mayfield song, “Keep on Pushing” which established him as one of the first R & B singer-songwriters to bring social commentary to the pop charts. Other “anthems” followed: “People Get Ready,” “We’re A Winner”; all hit songs but with a life away from the charts. Martin Luther King Jr. made “Ready” and “Pushing” unofficial anthems for the Movement. A State Senator named Barack Obama gave the Keynote speech at the 2004 Democratic Convention. The music that brought him onstage was “Pushing.” “People Get Ready” has been recorded by over 100 artists, bringing royalties to the composer, the kind of homage businesslike Mayfield appreciated. He said this song “came from my church. I must have been in a very deep mood of that type of religious inspiration when I wrote that song.” “We’re a Winner” (1967) was stronger in its lyrics, so much so that some radio stations would not play it during that year’s rioting.

Mayfield was uncomfortable when people called him “The Preacher” or “The Reverend” because of his new music, remaining modest and clear eyed about it, “I’m an entertainer first,” he often stated. Through my way of writing I was capable of being able to say these things and yet not make a person feel as though they’re being preached at.”

Mayfield was now moonlighting as producer for Okeh Records working with Major Lance, Gene Chandler and other chart names. In 1968 he started Curtom Records. Here he was in control of his recording, song publishing and recording studio. Control was important to Mayfield as he told Jerry Butler: “I just want to own as much of me as possible.’” The high school dropout knew how to take care of business and the present day music industry is notable for African American recording stars in charge of business enterprises - Jay Z., Kanye West, Dr. Dre, P. Diddy, Russell Simmons, etc. – can be traced back to Mayfield. He showed that successful Black Capitalism was possible, perhaps necessary.

The 1970s began and so did another transformative move for Mayfield – going to the movies. The period of “Blaxploitation” movies had started, films quickly produced, low budget and beamed to a black inner city audiences. They needed the right music on the soundtrack. At this time there was a not-exactly-unspoken question in Hollywood, “Can African Americans write film music?” Mayfield answered: “We showed that you didn’t need a room the size of a football field to lay music in. You didn’t have to be a Henry Mancini.” (He was now recording in a tiny demo. producing studio bought from RCA Records in Chicago).

“Super Fly” was a Blaxploitation movie, full of drugs, violence, and badass culture. Someone thought Mayfield’s soul funk grooves ideal for the soundtrack. That someone was not Mayfield who was no fan of the movie’s characters or plot… until he saw a way to subvert them. Altheida Mayfield says: “Curtis thought ‘Super Fly’ was a commercial to sell cocaine.” Songs for “Super Fly” came out and ran counterpoint to onscreen action – “Freddie’s Dead,” “Super Fly” (both million selling singles) , “Pusherman,” “Little Child Runnin’ Wild”. These songs would show up decades later; the Generation R(ap) discovered the art of sampling.

The Impressions’ “Super Fly” album became an instant classic of 1970s soul and funk, a rare example of a soundtrack outselling the movie and, along with Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder, Mayfield had introduced soul funk music that also said something, a groove that was socially aware. Movie work now took up much of Mayfield’s time – Gladys Knight and the Pips (the film “Claudine”), Aretha Franklin (“Sparkle”), Staple Singers (“Let’s Do It Again”), Mavis Staples (“A Piece of the Action”). “Short Eyes” had a 1977 hit for Mayfield himself.

By 1980 Mayfield had moved, with his family of six children, from Chicago to Atlanta, effectively bringing the Chicago Soul era to a close. His career was that of writer/producer for himself and other artists. He toured the U.S. Japan and Europe, especially Britain. Mayfield even revisited “Super Fly” in 1990 with “Super Fly 1990,” new songs and collaboration between Mayfield and Ice T. The rappers were finding Mayfield a major influence.

Then came August 13, 1990 and tragedy. Mayfield arrived for a Brooklyn, NY. concert sound check. On a rain swept afternoon, high winds toppled a lighting rig. He was trapped underneath, his spine crushed in three places, paralyzing him from the neck down. He was now wheelchair bound. If he had little control over his body though, he still controlled his career. Slowly at first, some strength returned but it was four years before he sang again in public. This was enough to convince him he should get back to recording. The result was his last album, “New World Order,” his last great song, “Here but I’m Gone,” original music recorded in his home studio under great pressure.

But Mayfield’s physical condition now truly began to deteriorate - diabetes forced the amputation of his right leg – and he died, December 26, 1999. Following his death, any number of tributes were mounted, accolades given. But the real tribute lay in the lasting power of the work he left behind, still being discovered and played by each new generation.