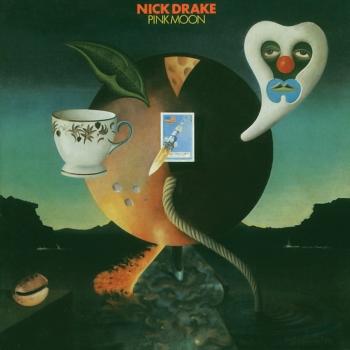

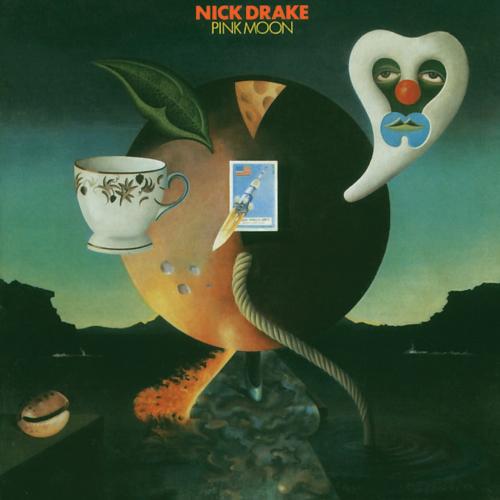

Pink Moon (Remastered) Nick Drake

Album info

Album-Release:

1972

HRA-Release:

09.07.2021

Album including Album cover

I`m sorry!

Dear HIGHRESAUDIO Visitor,

due to territorial constraints and also different releases dates in each country you currently can`t purchase this album. We are updating our release dates twice a week. So, please feel free to check from time-to-time, if the album is available for your country.

We suggest, that you bookmark the album and use our Short List function.

Thank you for your understanding and patience.

Yours sincerely, HIGHRESAUDIO

- 1 Pink Moon 02:03

- 2 Place To Be 02:41

- 3 Road 01:59

- 4 Which Will 02:56

- 5 Horn 01:21

- 6 Things Behind The Sun 03:56

- 7 Know 02:23

- 8 Parasite 03:33

- 9 Free Ride 03:02

- 10 Harvest Breed 01:36

- 11 From The Morning 02:34

Info for Pink Moon (Remastered)

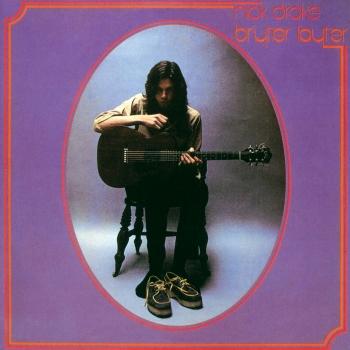

Nick’s penultimate album, capturing the zeitgeist of 1972, a stripped bare 28 minute masterpiece, but, at the time, his worst selling album. Co-produced by Nick Drake and John Wood and released on Island Records.

Pink Moon is the third and final album by Nick Drake, released on February 25, 1972. Initially, it garnered a small amount of critical attention, but decades after Drake's death it received widespread public and critical acclaim. In 2003, the album was ranked number 320 on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time.

Pink Moon was recorded at midnight in two separate two-hour sessions at Sound Techniques, with just Nick with engineer John Wood present. It features only Nick Drake's vocals and guitar, as well as some piano later overdubbed by Drake on the title track. Nick had apparently voiced dissatisfaction with Bryter Layter and had been talking for some time about recording a simple album with stripped down arrangements.

The results of those solo sessions were as harrowing and stark as anything by Robert Johnson or Charley Patton. Enclosed in an inner world of psychological distress, Drake recorded Pink Moon's dispatches from a private hell that was simultaneously terrifying and beautiful. Both the lyrics and the melodic motifs are pared to the bone here, their simplicity making them all the more immediately striking. The most nakedly emotional and disturbing moment is probably 'Parasite,' a visceral-but-mysterious account of a disconsolate soul roaming through the world in search of succor, with Drake taking the starring role, ultimately offering, 'take a look, you may see me in the dirt.' This was the end of the road for Nick Drake in more ways than one, but just the beginning for the scores of songwriters subsequently inspired by his bleak-but-beautiful visions.

„Pink Moon is folk icon Nick Drake's third and last full album — and at less than thirty minutes, it can seem as starkly foreshortened as the singer's life, which ended in 1974 when he was twenty-six. But as one of Drake's friends put it, 'If something's that intense, it can't be measured in minutes.' Rousing himself out of one of the paralyzing depressions that plagued him in his last years, Drake recorded these eleven tracks in two nights, often in just one take. He accompanies himself only on acoustic guitar, except for the title track, on which he overdubs a brief, lovely piano part.

By the time of these sessions, Drake had retreated so deeply into his own internal world that it is difficult to say what the songs are 'about.' His lyrics are so compressed as to be kind of folkloric haikus, almost childishly simple in their structure ('Which will you go for/Which will you love') and elemental in their imagery ('And I was green, greener than the hill/ Where flowers grow and the sun shone still'). His voice conveys, in its moans and breathy whispers, an alluring sensuality, but he sings as if he were viewing his life from a great, unbridgeable distance. That element of detachment is chilling. To reinforce it, messages of isolation gradually float to the surface of the songs' spare, eloquent melodies. 'You can say the sun is shining if you really want to,' he sings on 'Road,' as if daylight were merely a subjective perception that he could not summon the will to sustain. 'I can see the moon and it seems so clear.' 'I'm darker than the deepest sea,' he observes in 'Place to Be.'

It makes unfortunate sense in this age of marketing that what has partially rescued Drake from a quarter-century of obscurity is neither the admiration of artists ranging from R.E.M. to Elton John nor the generations of critics who have sung his praises, but a Volkswagen ad. Lack of recognition in his lifetime deepened Drake's constitutional despair and may well have contributed to his death from a (possibly intentional) drug overdose. He despised commercialism, of course, but let's hope that wherever he is, he can at least enjoy the irony.“ (Anthony Decurtis, Rolling Stone)

Nick Drake, vocals, piano, acoustic guitar

Produced by John Wood

Engineered by Nick Drake and John Wood at Sound Techniques

Mixed by John Wood

Mastered by Adam Dunn

Re-mastered by John Wood

Nick Drake(19 June 1948 – 25 November 1974)

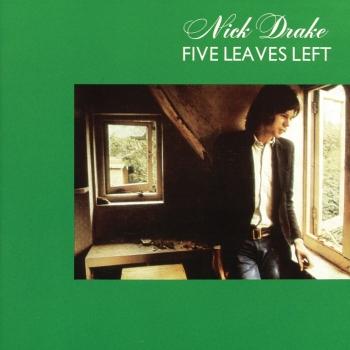

With every passing year, it becomes a little less accurate to say that Nick Drake has a cult following. Cults, by their very nature, tend to exist on the margins, the subject of their admiration unknown or even unloved by the vast majority of people. Mention Nick Drake to a certain generation of music fan and chances are you won’t have to explain yourself. Latterly, Drake’s name has become a byword for a certain kind of acoustic music. Gentility, melancholia and a seemingly casual mastery of the fretboard – in the minds of many listeners, any combination of these traits warrants comparison to Nick Drake. As a result, Drake is perpetually referenced across the reviews sections of every music title. That quite often the records in question bear no meaningful resemblance to Drake’s music speaks volumes. His legacy may, in one sense, be huge. But there’s painfully little of it: just three complete albums – Five Leaves Left (1969), Bryter Layter (1970), Pink Moon (1972) and a final quintet of songs recorded shortly before his death. As his relevance increases, so does an insatiable communal yearning for their source to yield more. Hence the constant namechecks. Hence the constant repackaging and remixing of the same old bootleg recordings. Somehow we cannot quite accept the fact that this was all he left behind.

Such a turn of events isn’t without a certain irony. Towards the end of his life, Drake appeared to long for the vindication that comes with commercial success. And yet he seemed incapable of compromising himself to the pursuit of recognition. His shyness made interviews difficult. Live performances became increasingly rare. When recording music, the only compass he used was his own intuition. For Five Leaves left, he asserted himself when he needed to – dispensing with the arranger suggested by Joe Boyd and replacing him with his old Cambridge associate Robert Kirby. Pink Moon was just Drake and a guitar, an exercise in intricate desolation, no less perfect for its stark brevity. Commercial success may not have vindicated him, but the intervening years certainly have. Ten years ago, he entered the Billboard 100 (and the Amazon Top Five) for the first time. Thirty seconds of Pink Moon used in a Volkswagen advert alerted America to the otherworldly magic of Drake’s hushed English tones. His friend and label-mate Linda Thompson recalls recently hearing the song in LA over a supermarket tannoy: “I couldn’t believe how amazing, how right it sounded. How did he know?” Writing about Drake, the late Ian McDonald attempted to put into words why Drake’s music should have achieved such a relevance in the century after its creator brought it into being. In a celebrated essay, McDonald posited the suggestion that songs such as River Man and Way To Blue reconnect us with a part of our selves that modern life has all but eroded away. Certainly, much of his music is endowed with a peculiar prescience. Over arrangements that seem to mimic the bustle of a world moving too fast, the prescient Hazey Jane II sees Drake impishly enquiring, “And what will happen in the morning when the world it gets/So crowded that you can’t look out the window in the morning.”

The manner in which Drake’s life ended has inevitably coloured the way his songs are perceived: among them, the haunting Black-Eyed Dog and the self-mocking Poor Boy. “Don’t you worry,” he sings on Fruit Tree, “They’ll stand and stare when you’re gone.” In the liner notes to 1994’s Way To Blue compilation, Drake’s producer and mentor Joe Boyd commented that, “listening to his lyrics… he may have planned it all this way.” His point – that the best music will always invite conjecture and speculation about its authors – is well made. But at the same time, it should be added that the sadness in Nick Drake’s songs was frequently the corollary of an all-consuming joy. As often as not, both extremes are to be found within the same song: the autumnal languor of I Was Made To Love Magic; the life-affirming brush-strokes of Northern Sky (“I’ve never felt magic as crazy as this”). Records born exclusively of misery and catharsis can do little other than depress their listeners. Their candour may garner critical bouquets but they rarely return to the CD tray. Drake certainly suffered from depression – most notably in the latter two years of his life – but his music was not a function of that depression. Richard Thompson who played on Five Leaves Left and Bryter Later remembers a quiet character, though not a miserable one: “I remember long silences, but they were never oppressive. With Nick, you sensed [that] very little needed to be said that couldn’t be said with a guitar in his hand.” As Drake puts it on Hazey Jane II, “If songs were lines/In a conversation/The situation would be fine.”

Thirty three years have now passed since Nick Drake’s death. Original pressings of his records change hands for around £200. Dedicated fanzines and websites continue to interpret and second-guess every note and utterance. The bucolic village of Tanworth-In-Arden, where Drake grew up, attracts a steady trickle of visitors – somehow seeking to climb further inside the music. And yet as his father Rodney recalled, “And I remember in one of his reports towards the end of the time at his first school, the headmaster… said at the end that none of us seemed to know him very well. And I think that was it. All the way through with Nick. People didn’t know him very much.” It’s impossible to keep count of the contemporary artists who cite Drake as an inspiration, but a cursory round-up includes R.E.M., Snow Patrol, Norah Jones, Radiohead, Brad Pitt, Sam Mendes, Paul Weller, Keane, Portishead, Belle And Sebastian, The Coral, Coldplay, Heath Ledger, David Gray, Super Furry Animals and Beth Orton. Along with household names of his creative lifetime – the Stones, The Beatles, Marley, Hendrix – his albums have become an unofficial set text for anyone passionate about music.

In 2012, he has become so much more than the sum total of his work. The greater our fascination with him, the more we reveal about ourselves. In this sense, maybe Ian McDonald was right. Perhaps his music allows us to feel a little less like, as Drake put it, “a remnant of something that’s passed.”

This album contains no booklet.